Accountability At-Large

At-large seats on City Council were created 100 years ago. They need to go away.

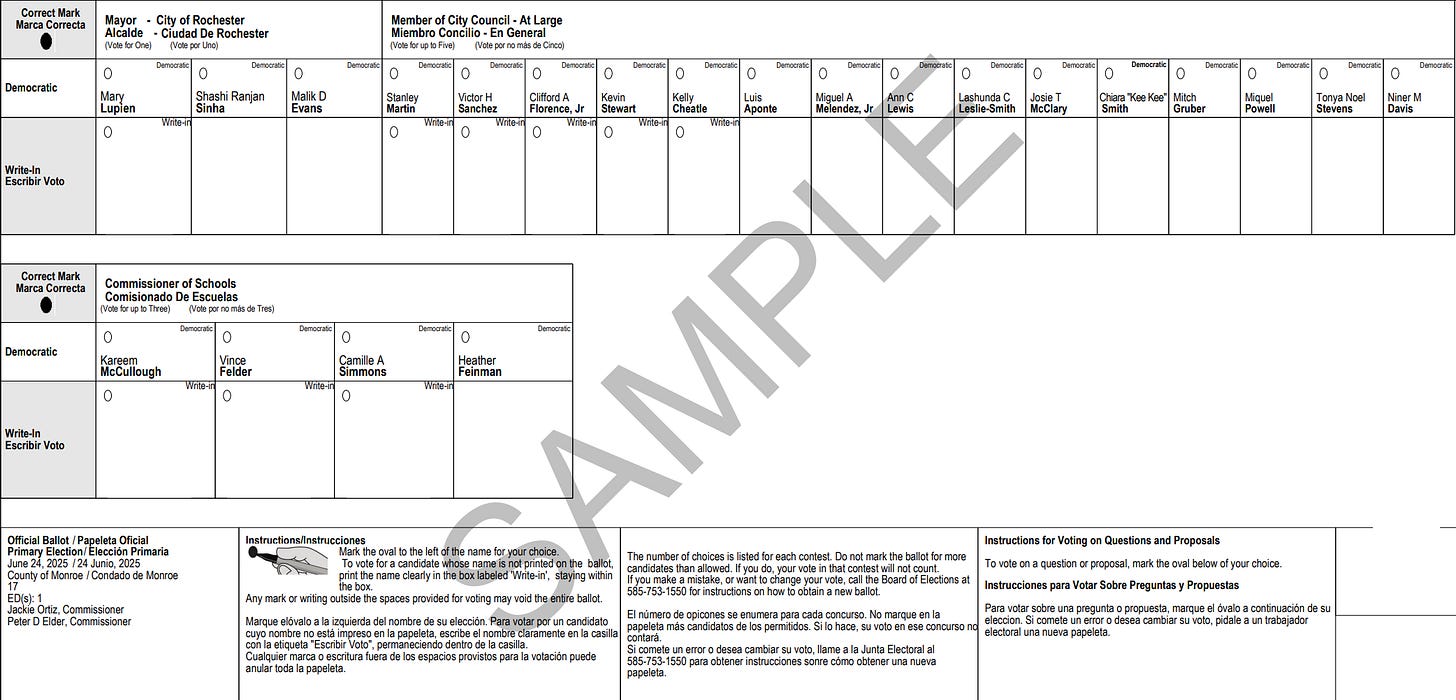

There are 15 candidates on the ballot for five at-large Rochester City Council seats. That means a three-and-a-half-month sprint to educate voters about 15 different candidates — and for candidates, a near-impossible challenge of breaking through the noise without massive resources.

This is not how a healthy democracy should function.

The current structure of our City Council — five at-large seats and four district seats — dates back to 1925. That’s when Rochester, like many cities of the time, was restructured to prioritize government efficiency over representation. The goal was to professionalize city government and insulate it from the influence of corrupt political machines.1 But what may have made sense in a more homogenous, less diverse Rochester a century ago is badly outdated today.

The result is that Rochester is now an outlier among major New York cities. No other city gives at-large seats as much weight. Most cities our size rely more heavily on district-based representation — because it’s fairer, more responsive, and more democratic.

At-large seats are designed to represent the whole city. But in practice, they often dilute the voices of specific neighborhoods, racial and ethnic minorities, and grassroots political movements. When five of nine seats are decided in a citywide vote — and the Democratic primary is effectively the general election — party leaders and special interests wield enormous power in deciding who gets elected. That’s because winning a citywide race requires a lot more resources than winning a district race.

From a governing standpoint, at-large seats confuse residents. At-large members often defer neighborhood issues to district members. Meanwhile, each district council member represents roughly 50,000 people — too many for meaningful day-to-day relationships with constituents. Shifting to nine district seats would cut that number in half, allowing for deeper connections and more accountability. While some warn that additional district seats could foster parochialism, cities across the country function effectively with district-based councils.

And let’s be honest: the sheer number of candidates on the ballot is a barrier in itself. Voters shouldn’t need to research 15 people just to fill out a primary ballot. The current system sets up campaigns that are expensive, unwieldy, and inaccessible to everyday residents without insider support.2

It’s been 41 years since Rochester last revised its governmental structure, moving from a city manager to an elected mayor system. (The council structure was not changed.) At the time, the Democrat and Chronicle editorial board assured voters that “electing a mayor won’t be electing a political boss” because City Council could act as a check on executive power. But in a one-party town, that promise has proven hollow. Today, as long as the mayor has five loyal votes, there is little meaningful oversight or dissent.3 The Council often functions more like a philanthropic or corporate board than a legislative body tasked with holding the executive accountable. In one recent exchange, when Councilmember Stanley Martin expressed frustration about not receiving answers from the mayor’s office regarding an event she was hosting, Mayor Malik Evans responded, “I don’t know if you think I report to you or something like that, but that’s not the case.”4

The mayor is now running a slate of five at-large candidates — some with serious conflicts of interest that would make challenging the administration unlikely. Backed by significant fundraising advantages, this slate exemplifies how the at-large system consolidates power and limits independent voices.

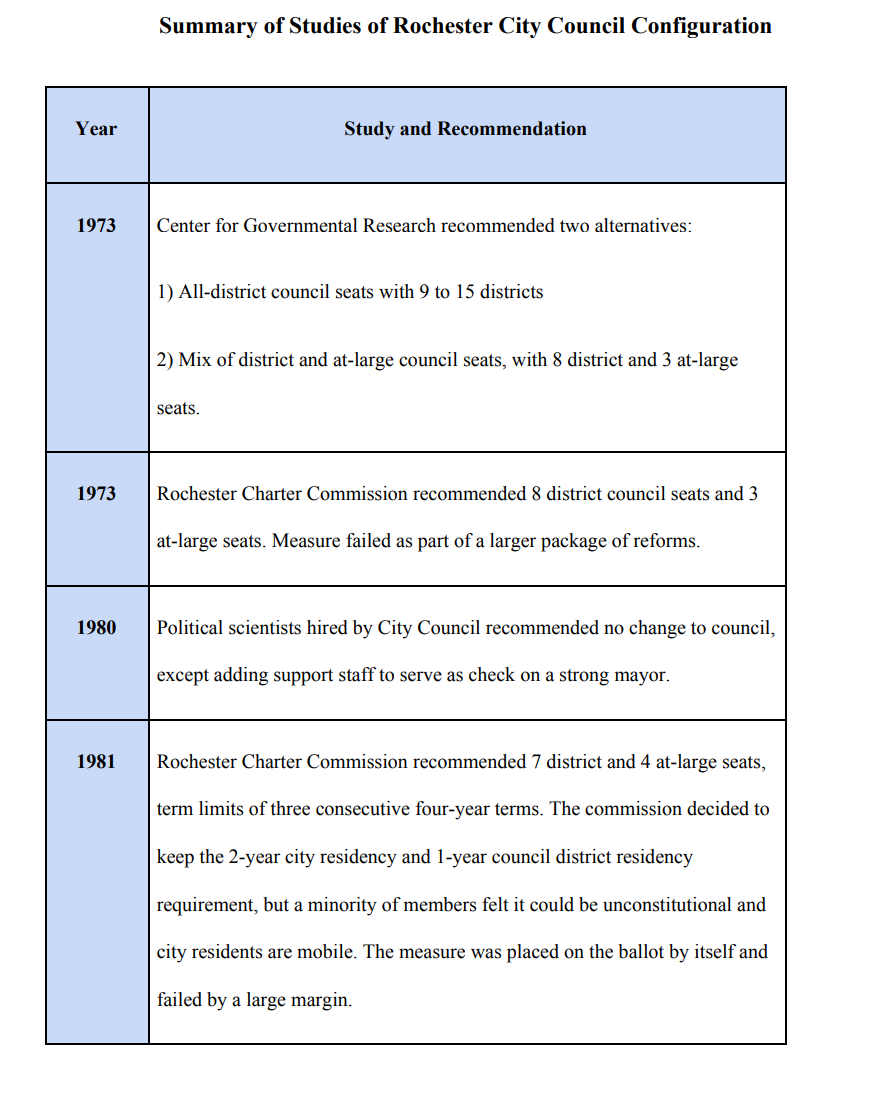

We don’t have to keep doing things this way. In fact, a series of studies back in the 1970s in 1980s suggested doing away with a majority at-large council seats:

Rochester deserves a modern, representative City Council — one that reflects its neighborhoods and amplifies the voices of its people. It's time to revisit the structure of our government and commit to reforms that prioritize democracy.

The new charter mandated nonpartisan elections, but that provision was struck down in court.

A ranked choice voting and runoff system better accommodates multi-candidate elections. Rochester does not have such a system.

A notable exception was council’s investigation into the Warren aministration’s handling of the Daniel Prude case, an extraordinary situation and a shining moment for legislative oversight.

I was wondering as I was reading if you'd introduce the rank choice in here. Perhaps the answers lay in some at large but with diminished influence behind the districts. Priority to districts, such that the at large is 25% range of the total. I think there is perhaps a case to be made for city wide representation in order to provide a wider perspective, but also to not allow it to overshadow the more particular representation that is important. From an outside perspective having the interests of the whole seems important but not at the dismissal of the particular unique interests.